PHOTO RAW, may 2012

the Most precious thing

“What is the future for children without dreams?”

Kids with responsibilities

Łukasz Sokół realised that dream belong to well-off children

Text Tina Kirkas

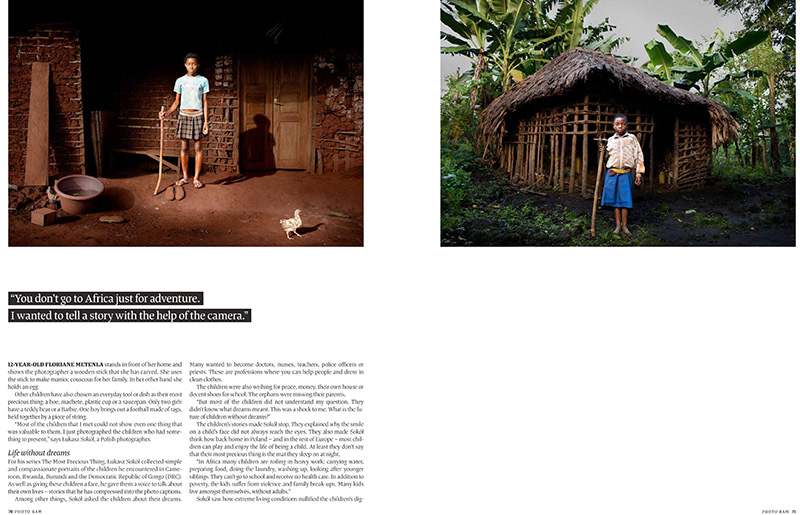

12-year-old Floriane Metenla stands in front of her home and shows the photographer a wooden stick that she has carved. She uses the stick to make manioc couscous for her family. In her other hand she holds an egg.

Other children have also chosen an everyday tool or dish as their most precious thing: a hoe, machete, plastic cup or a saucepan. Only two girls have a teddy bear or a Barbie. One boy brings out a football made of rags, held together by a piece of string.

“Most of the children that I met could not show even one thing that was valuable to them. I just photographed the children who had some- thing to present,” says Łukasz Sokół, a Polish photographer.

Life without dreams

For his series The Most Precious Thing, Łukasz Sokół collected simple and compassionate portraits of the children he encountered in Came- roon, Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). As well as giving these children a face, he gave them a voice to talk about their own lives – stories that he has compressed into the photo captions.

Among other things, Sokół asked the children about their dreams.

Many wanted to become doctors, nurses, teachers, police officers or priests. These are professions where you can help people and dress in clean clothes.

The children were also wishing for peace, money, their own house or decent shoes for school. The orphans were missing their parents.

“But most of the children did not understand my question. They didn’t know what dreams meant. This was a shock to me. What is the fu- ture of children without dreams?”

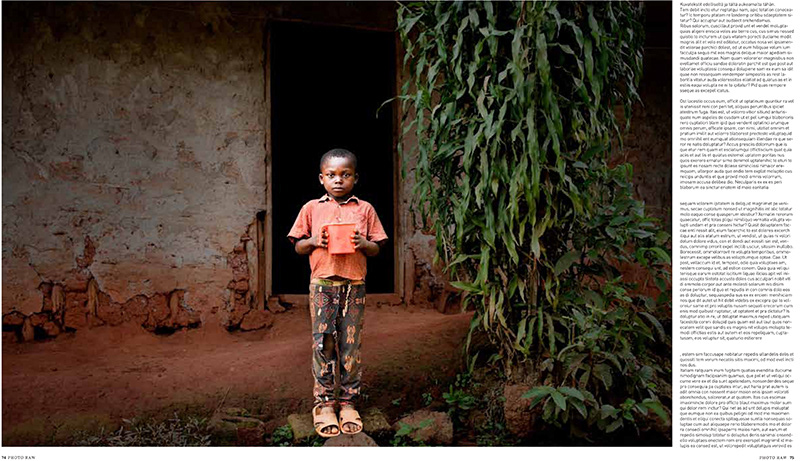

The children’s stories made Sokół stop. They explained why the smile on a child’s face did not always reach the eyes. They also made Sokół think how back home in Poland – and in the rest of Europe – most chil- dren can play and enjoy the life of being a child. At least they don’t say that their most precious thing is the mat they sleep on at night.

“In Africa many children are toiling in heavy work: carrying water, preparing food, doing the laundry, washing up, looking after younger siblings. They can’t go to school and receive no health care. In addition to poverty, the kids suffer from violence and family break-ups. Many kids live amongst themselves, without adults.”

Sokół saw how extreme living conditions nullified the children’s dignity as humans and stunted their opportunities for growth. At the same time some of the children, even the smallest ones, took on responsibili- ties far beyond their years.

“In DRC I met 15-year-old Sebishimbo Sibomana, whose mother had died five years ago and his father much earlier. Now the boy is taking care of his disabled ten-year-old brother and after school he is farming beans on a plot of land rented from a coffee company.”

Confusing Africa

Łukasz Sokół waited a long time for his first trip to Africa. For years he had been dreaming about the continent that the Polish journalist and author Ryszard Kapuściński described with a warm heart, without judg- ing. Like Kapuściński, Sokół wanted to experience Africa close to the people.

“You don’t go to Africa just for adventure. There has to be a reason for the journey. I wanted to tell a story with the help of the camera.”

Finally in 2009 Sokół got the chance to spend a month in Cameroon with a friend who worked in a Polish aid organisation. He raised the money for the trip by selling his car. Once there, he documented the lives of the Polish missionaries and local people for his series Mission. Along- side this project he produced the images of the children and their most precious things.

“Without my friend and his contacts I would not have had access to all the places I visited. With the help of the missionary workers I also got close to the local people. I could not have managed it by myself.”

The following year Sokół spent a month taking pictures in Rwanda, Burundi and DRC. He was surprised by the differences between the neighbouring countries.

“The houses and the tools looked similar but the people and their at- titudes and even their consciousness differed considerably from each other.”

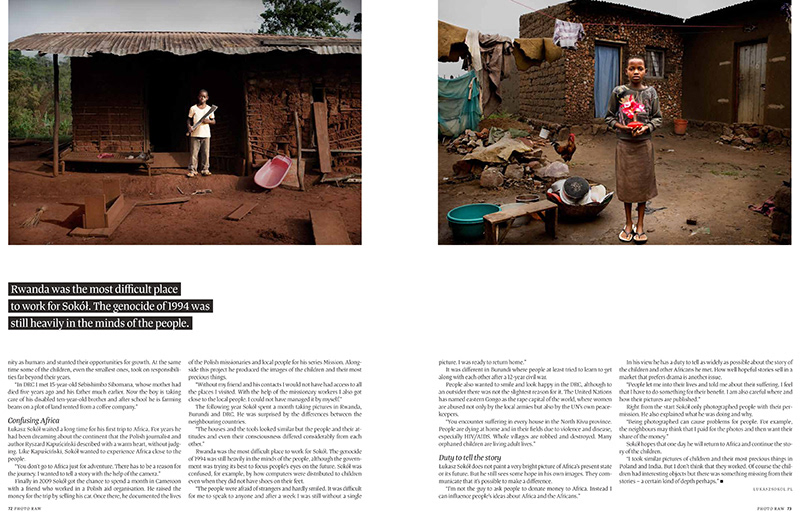

Rwanda was the most difficult place to work for Sokół. The genocide of 1994 was still heavily in the minds of the people, although the govern- ment was trying its best to focus people’s eyes on the future. Sokół was confused, for example, by how computers were distributed to children even when they did not have shoes on their feet.

“The people were afraid of strangers and hardly smiled. It was difficult for me to speak to anyone and after a week I was still without a single

picture. I was ready to return home.”It was different in Burundi where people at least tried to learn to get

along with each other after a 12-year civil war.People also wanted to smile and look happy in the DRC, although to

an outsider there was not the slightest reason for it. The United Nations has named eastern Congo as the rape capital of the world, where women are abused not only by the local armies but also by the UN’s own peace- keepers.

“You encounter suffering in every house in the North Kivu province. People are dying at home and in their fields due to violence and disease, especially HIV/AIDS. Whole villages are robbed and destroyed. Many orphaned children are living adult lives.”

Duty to tell the story

Łukasz Sokół does not paint a very bright picture of Africa’s present state or its future. But he still sees some hope in his own images. They com- municate that it’s possible to make a difference.

“I’m not the guy to ask people to donate money to Africa. Instead I can influence people’s ideas about Africa and the Africans.”

In his view he has a duty to tell as widely as possible about the story of the children and other Africans he met. How well hopeful stories sell in a market that prefers drama is another issue.

“People let me into their lives and told me about their suffering. I feel that I have to do something for their benefit. I am also careful where and how their pictures are published.”

Right from the start Sokół only photographed people with their per- mission. He also explained what he was doing and why.

“Being photographed can cause problems for people. For example, the neighbours may think that I paid for the photos and then want their share of the money.”

Sokół hopes that one day he will return to Africa and continue the story of the children.

“I took similar pictures of children and their most precious things in Poland and India. But I don’t think that they worked. Of course the chil- dren had interesting objects but there was something missing from their stories – a certain kind of depth perhaps.”